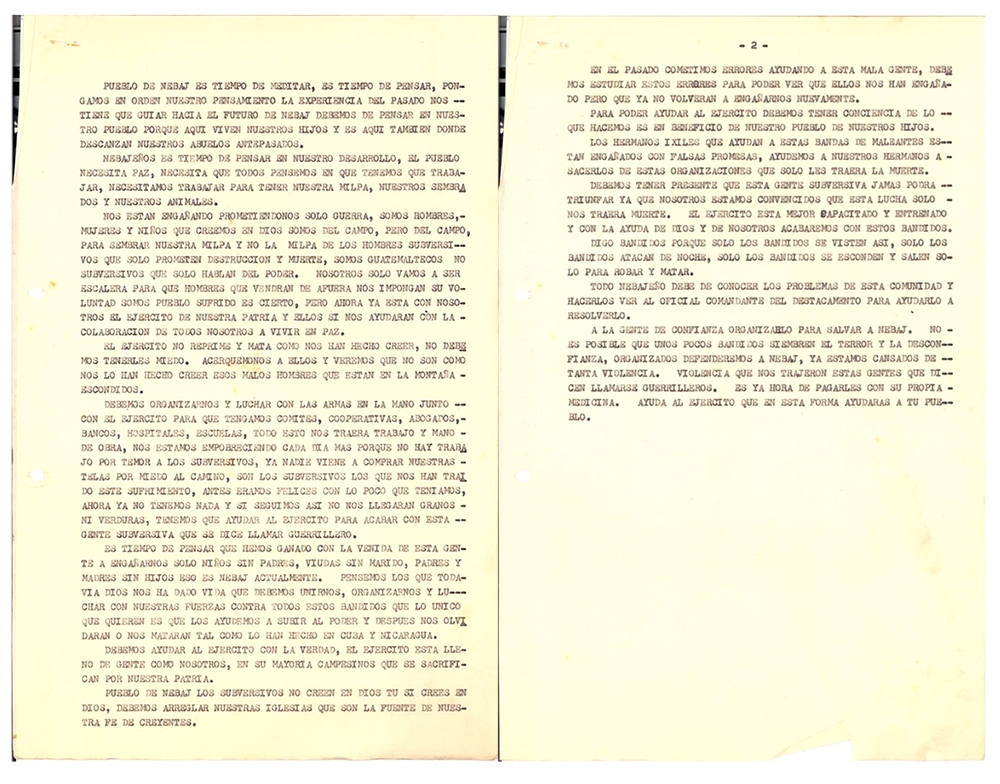

Installation view at Centro Cultural de España, Mexico City.

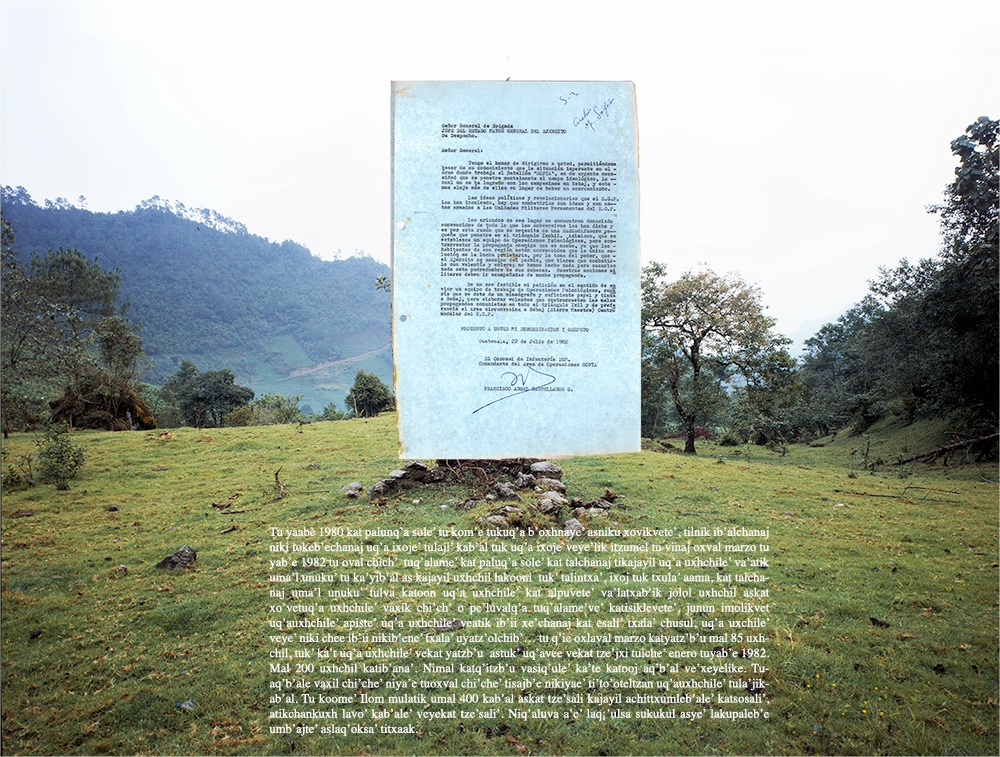

At the start of the 1980s, Central America had become one of the strategic hotspots of the geopolitics of Cold War. It was also one of the bloodiest times in the Guatemalan civil war. By then the Guatemalan State developed a military plan to annihilate the guerrilla’s social rural bases. This counterinsurgent offensive was named the Tierra Arrasada (Scorched Earth) strategy. It was an exercise in ethnic cleansing in which the Guatemalan army used excessive violence to sweep away over four hundred native communities. Today nothing appears to remain where those settlements once stood; houses were rebuilt years later on the outskirts, the inhabitants relocated to far-off places or the villages simply ceased to exist.

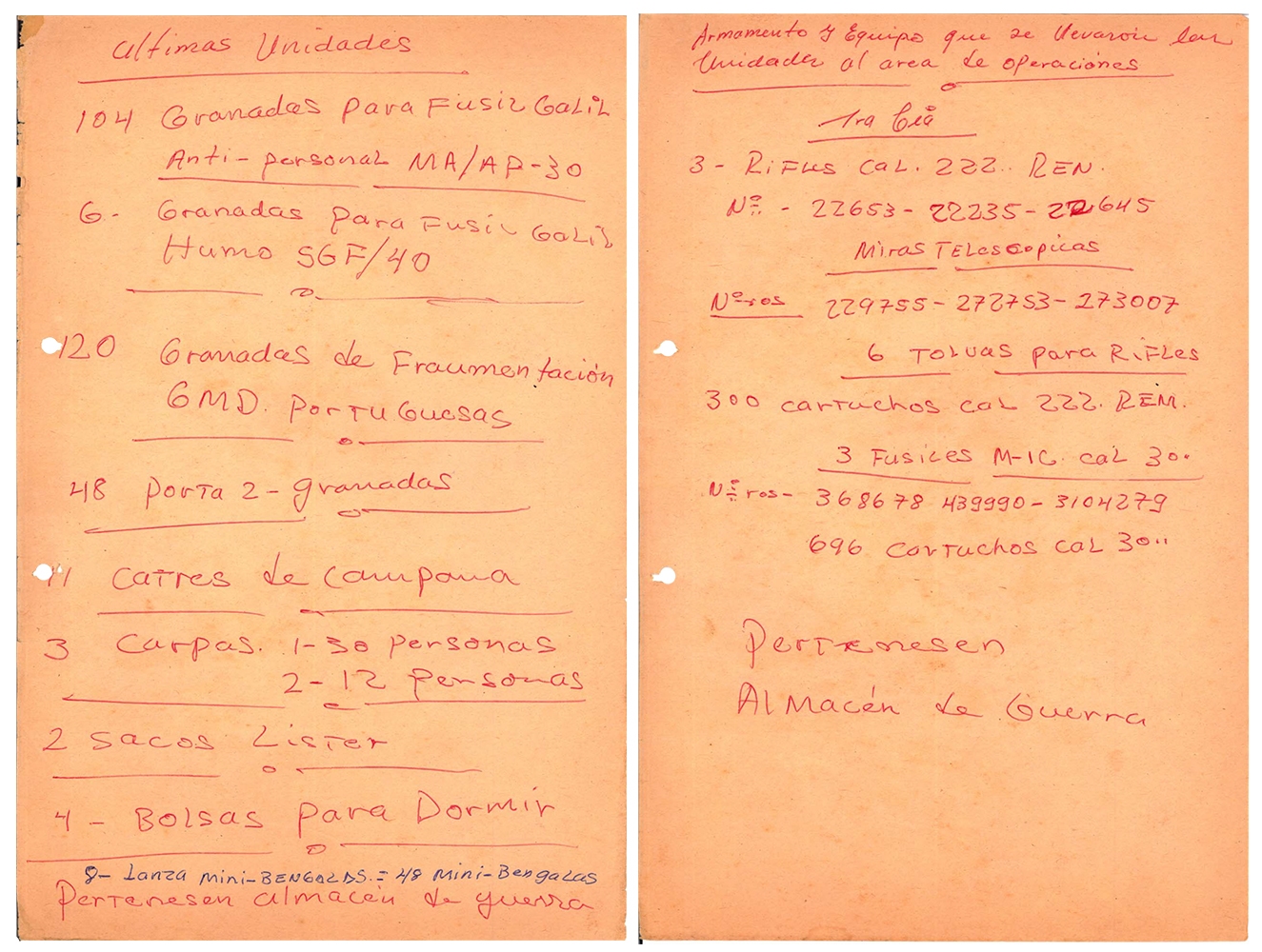

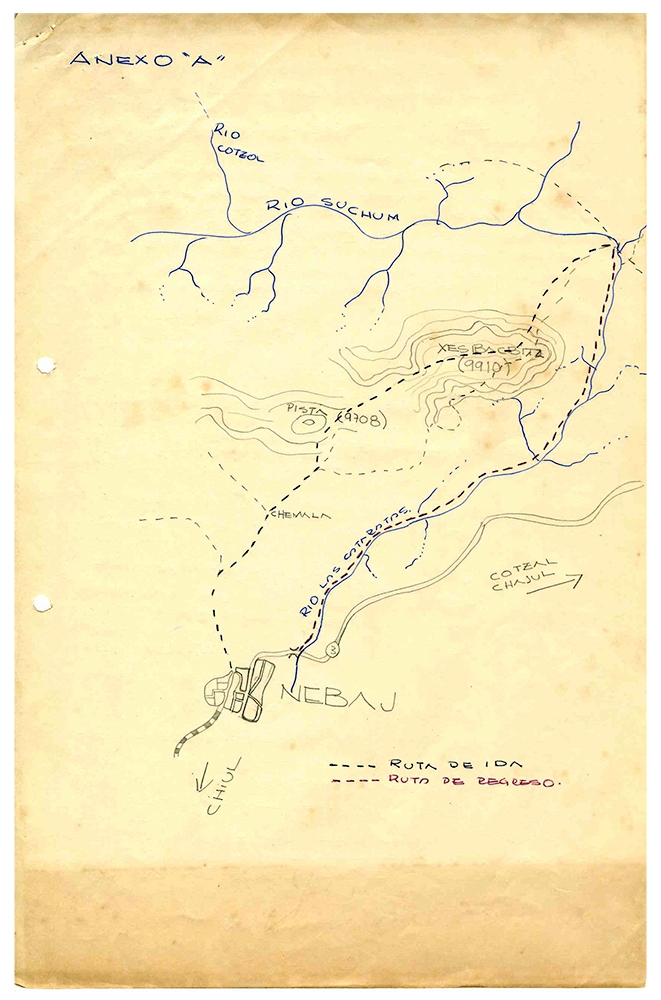

The pieces that this project is comprised of, photographs and texts initially destined to the large format and gallery walls, function as records about these deserted places and what happened in them. The photographies are unaffected landscapes and locations. Also, they exhibit a tale not unknown to the author who in those years faced the other side of repression, that of the city, and who was forced into a perennial exile. The Tierra Arrasada project seeks, in vain, to work off a personal debt. This project’s reason for being lies in the confrontation of the amnesia and historic omission of a past common to us all, human in its most elemental form: two hundred thousand people died in the Guatemalan armed conflict, more than the wars and dictatorships of El Salvador, Nicaragua, Chile and Argentina combined. About eighty five percent of those killed were indigenous people.

The titles of the photographic pieces correspond to the names of the communities of each razed place. Each of them has an excerpt or the entire testimony of those who lived or witnessed what happened in the portrayed spaces. The video piece depicts a place and the story attached to the landscape.

***

A inicios de la década de mil novecientos ochenta Centro América es una de las arenas estratégicas de la Guerra Fría. En Guatemala se libra entonces el momento más cruento de la guerra civil. Con apoyo financiero estadounidense y logístico israelí el Estado guatemalteco lleva a cabo un plan militar encaminado a aniquilar la base social rural de la guerrilla. A esta ofensiva contrainsurgente se le dio el título de estrategia de Tierra Arrasada. Fue un ejercicio de limpieza étnica en el que el ejército guatemalteco con lujo de violencia barrió con más de cuatrocientas comunidades indígenas. Hoy día, donde antes se localizaron poblados en apariencia no queda nada; las casas se reedificaron años después en las cercanías, sus habitantes se reubicaron en zonas distantes, o simplemente las aldeas en cuestión dejaron de existir.

Las piezas que comprenden este proyecto, cuadros fotográficos, cuadros de texto, y una videoinstalación, operan como documentos sobre esos sitios desiertos y lo acontecido en ellos. Son paisajes, locaciones, y textos sin artificio. Exhiben un relato no ajeno al autor, quien en esos años y desde el otro polo de la represión, la ciudad, sale de Guatemala hacia un exilio perenne. El proyecto Tierra Arrasada busca en vano dirimir una deuda personal. Su razón se ubica en la impronta que opone a la amnesia y la omisión históricas a propósito de un pasado común a todos, humano en su noción más elemental: doscientas mil personas murieron en el conflicto armado guatemalteco, más que en las guerras y dictaduras de El Salvador, Nicaragua, Chile y Argentina juntas. Cerca del ochenta y cinco por ciento de los que murieron eran indígenas.

El título de las piezas de fotografía corresponde al nombre de la comunidad donde se ubican las sitios arrasados. Cada una de ellas se adscribe a extractos de testimonios, o testimonios completos, de quienes vivieron u observaron lo que en los espacios representados sucedió.

Óscar Farfán, México D.F. 2010.

Pexlá

Kat uli’ tu mal u txala q’i jueves, kat i y’atz uq’a uxchile’ kat iy’atz’ uq’a q’esla aama, ixoj ve tuk i ya’bil, tuk talintx’a kat ulchan unpajte’tu ich’e u septiembre, nimalchit q’ii kat juplo tu tostixh, naj tuk ixoj. Kat i nuk tib’ umal oval mil o cajval mil Chaxi’chalanaje’ nimal q’ii kat’i b’an chanaj, tulkat tilchanaj ye’nikitza’jvet unq’a tale’kat texhb’u vet inq’a q’ixime, kati paxi’ unq’a ku la’je tuk k’u pichele’. Ti motxtel kat telq’a ku puaj unq’a uxchile’, tunq’a q’ieve’ kat yatzpu’ vinqi’l uxchile’ kat jupx’o b’eluval q’ii tetz septiembre tu yab’e 1981 kat chajb’elveto’ tu junlaval tachb’al ich’ u septiembre.

***

Vinieron un Jueves Santo y mataron a la gente. Mataron a ancianos, mujeres embarazadas y niños. Vinieron otra vez en septiembre. Por varios días nos encerraron en la iglesia a hombres y mujeres. Se juntaron como cinco mil o cuatro mil soldados. Se quedaron por un buen tiempo, al ver tal vez que no les alcanzaba la comida, se comieron nuestras vacas, cerdos, chivos, nuestro maíz, quebraron nuestros platos y vasos. Por ultimo se robaron el dinero de la gente. Esa vez masacraron como a veinte personas. Nos encerraron el nueve de septiembre de 1981 y nos soltaron el once de ese mismo mes.

***

They came on Holy Thursday and killed people. They killed elderly people, pregnant women and children. They came again in September. For several days they shut us men and women in the church. Four or five thousand soldiers gathered. They stayed for a while, and when they saw their food wasn’t enough they ate our cows, pigs, goats, our corn, they broke our dishes and glasses. Finally they stole people’s money. That time they massacred like twenty people. They locked us up on September 9th, 1981 and they released us on the 11th of the same month.

Miguel Ramírez Xel

Cocop

Uq’a b’axa kab’ale’ iliniktib’ asnachenchit ti’uq’a q’etze’, ye’q’otzalike uva’ aikuq’aa sole’ okuete kuxhnitelike veniq’avike kat q’ab’ivete ye’nikiya’ telvete’ kat talvet akunb’ale’ a’usole’, atik’o tukab’al ye’lo katb’eno’ kat atino’ tzitzi’, kat tal aakunb’ale’ silao’jo’ lakitalchanaj va’ob’oxhna’y. katq’ilvet usib’e tuq’a kab’ale’, kat talchavet akun b’ale’ unb’ajte’ valab’enveto’ ti’ub’aq’ch’ich’e nikitele’ a’e’b’a veniyatz’ chanaj uxhchil, tumuxtele katb’enveto’ kumujq’ib’ tutx’akab’en, tulva’ atik’o tutx’akab’en katq’il vetitz’euq’akab’ale’.

***

Las primeras casas estaban juntas y lejos de la nuestra, realmente no sabíamos si eran los soldados o eran petardos lo que se oía, pero cuando oímos que no dejaban de sonar mi padre dijo que eran soldados. Nos encontrábamos en la casa, no nos salimos, nos quedamos allí porque mi padre decía que si huíamos iban a pensar que éramos guerrilleros. Vimos el humo de las casas y luego mi padre dijo que mejor nos fuéramos porque por los disparos de seguro estaban matando a la gente. Al final nos fuimos a esconder a esas montañas. Desde allí veíamos todas las casas que se quemaban.

***

The first houses were together and far from ours. We didn’t really know if it was soldiers or firecrackers we were hearing, but once we heard that the sounds didn’t cease my father said they were soldiers. We were inside the house; we didn’t go out, we stayed there because my father said that if we ran away they would think we were guerrillas. We saw the smoke coming out of the houses and then my father said we had better leave, because by the sound of the shots they were surely killing people. In the end we went and hid in those mountains. From there we could see all the houses burning.

Juan Velasco

Kat ta’b’inajvatzike’ ub’aq’ch’iche’ niktele’ katul talnajsq’ej. Akun b’ale’ kat talaak yexhtikat lab’enkato’ ye’maj vaexh nukub’ane’, tu q’ievee q’ab’arelik aak ti’u nimlaq’ie tuxalaq’ii ye’isa’ak ib’ene’ akuxh uvitzi’n Lu’ tuk’in katb’enveto’ askat talvet akuntxutxe’ silab’eno’, lakuxeq’ib’, a’akunb’ale’ ye’katisa’ ib’ene’ kat kavetak tuk’aak astuk uq’a tz’ub’chalavitz’ine’ tukuq’a tixq’el uq’avatzike’ katkavet chaak tukab’al, askat b’envetin tuknaj vatzike’ tuk umatnaj ve xhun ib’ii vatzikchitvete’, oxvalo’ kat b’enveto’ xoluq’a tze’e’, kat q’ab’i telb’aq’ch’ich’ tunkab’al, katq’ab’i isikin uq’avitz’in vatzike’, katb’enveto’.

***

Mi hermano se enteró por los tiroteos y vino a avisarnos. Mi padre respondió que no íbamos a ningún lado porque no estábamos haciendo nada malo. Mi padre ese día estaba borracho por la fiesta de Semana Santa y no quiso irse. Sólo mi hermano Pedro y yo nos fuimos y mi madre dijo que si nos íbamos que tuviéramos cuidado, pero mi padre no quiso y se quedó con ella, mis hermanos pequeños y las esposas de mis hermanos. Se quedaron en la casa y mi hermano y yo nos fuimos con Juan, mi otro hermano, éramos tres y nos fuimos hacia la montaña. Oímos que llegaban los soldados, oímos los disparos en mi casa, oímos los gritos de mi familia y seguimos caminando.

***

My brother found out about the shootings and came to tell us. My father answered that we weren’t going anywhere because we weren’t doing anything wrong. My father was drunk that that day because of the Holy Week festivities and he didn’t want to leave. Only my brother Pedro and I left. My mother said that if we were leaving, we should be careful, but my father didn’t want to go so he stayed with her and my younger brothers and my brothers’ wives. They stayed in the house and my brother and I went with Juan, my other brother, it was the three of us and we went towards the mountain. We heard the soldiers arriving, we heard the shots in my house, we heard the screams of my family and we kept on walking.

Jacinto de Paz

Ilom

Uma’l u ixoq’ ve’ ni txa’q’on tzi’ a’ kat talsve uva in la b’eninn ta kab’ale as kat i yatz’ lu chanaj ti’ u kab’ale as kat iyatz’ lu chanaj aak un b’ale tuk aak un txutxe’, u vitz’ine, u vixqele’, tuk inq’a talintxa’e tumat unjie tulva’ yelik vet inq’a sole’ kat ulvet in tuka’b’al, tzaaj kuxh kat un lejvete’ tuk’ i yalich’io’l tze’najchitvete a kuxh utule’ nalikvete’ yelik vet i vatz, i q’ab’, tuk toj, ka’jayilik chit mat i tze’e. kat kuxh va vet kan tz’upul txava’ ye nik un tx’ak vatinikvete tzitzi, ye kat un tx’ak vet un mujatchaak, ka’at uxhchil kat mujuncha’ak ye’xh kam o’olvet vi’ camnaj, kat kuxh mujbuvet txala u ka’b’ale.

***

Una mujer que estaba lavando en el río me dijo que no me fuera a la casa porque los soldados la tenían rodeada, y que ya habían matado a mis padres, mi hermano, mi esposa y mis hijos. Al día siguiente que ya no estaban los soldados vine a la casa. Sólo encontré cenizas y restos de los cuerpos, todos calcinados, ya sólo se miraba el estómago, ya no tenían cara, manos y pies, todo estaba quemado. Ya sólo eché un poco de tierra encima de los cuerpos y me fui llorando porque no aguantaba estar allí. No aguantaba enterrarlos, así que otras personas lo hicieron. No los llevaron al cementerio, los enterraron aquí, al lado de la casa.

***

A woman who was doing laundry in the river told me not to go home because the soldiers had surrounded the house and already killed my parents, my brother, my wife and my children. The day after the soldiers left I went home. I found only ashes and the charred remains of bodies, only the torsos were left, they didn’t have faces, hands, feet, everything was burnt. I only threw a little bit of dirt over the corpses and ran away crying because I couldn’t stand being there. I couldn’t bear to bury them, so other people did. They didn’t take them to the graveyard; they buried them here, next to the house.

Francisco Guzmán

Vicalamá

Mujelikq’ib’ atiknimalxovichi’l sukuk’atz, akuxhuq’a Chaxi’chalanaje’ atik tukoom, ye’likvet uxhchil, asuq’a sole’ kat ilejchanaj akunq’eslauntxutxe’ tuk’ uma’l akun nan, ye’lik chaak tukab’al nikimujtib’ chaakjaq’tze’, ye’likchaak sukukatz’, askat ilejuq’asole’ chaak askatitilu’chanaj. Tulkatoon chanaj ve’atikatchaak. Akun q’eslauntxutxe’ katjub’alaak tuk’kaval b’aq’ch’ich’, uma’l kat oktutuul umate’ tzi’ib’ala’ katsutleliku’ vatzchanaj ye’katkujeb’ikulchanaj tiuve matikib’anatchanaj kat to’eltzanchanaj ch’ich’ ye’katvila’ kamchitu’ katib’anb’e askati tzo’kvas ichu’ akunq’eslauntxutxe’, echitzo’kb’u umajichib’il txoo, ti’toneb’etchanaj tuvastule’, katiz’ok chanaj vasiju’e’ tukvasitzi’e, nalikvastee. Echkat ulb’elakun nane’umb’ajte’. Xamtelkuxhkat q’ab’ivete’ vakatyatz’b’uchaak a’mujelikatq’ib’ jaltu’uk’ome

***

Estábamos escondidos porque teníamos mucho miedo. Sólo los soldados estaban en la aldea, ya no había gente. Mi abuela y una tía regresaron para acá por algo y los soldados las agarraron aquí donde estaba su casa. Les dispararon y las mataron. A mi abuela le dieron dos tiros, uno en el estomago y otro en la frente. Quedó tirada frente a ellos. Y no se conformaron con eso, con un cuchillo o machete, no sé qué fue exactamente lo que usaron, le cortaron los senos a mi abuela, como cortando carne de algún animal, hasta llegar al estómago, también le cortaron la nariz y la boca, se le miraban los dientes. A mi tía le hicieron lo mismo. Después fue que oímos que las habían matado.

***

We were hiding because we were very scared. Only the soldiers were in the village; there were no people there anymore. My grandmother and one of my aunts came back tu pick up something, and the soldiers found them and captured them. They shot and killed them. My grandmother was shot twice, once in the stomach and once in the forehead, she ended up lying in front of them, and they weren’t satisfied with what they’d done to her, they pulled out a knife or a machete, I don’t know exactly what they used and they cut my grandmother’s breasts, like cutting some animal’s meat, until they reached the stomach, they also cut her nose and her mouth, you could see her teeth. They did the same thing to my aunt. We learned later that they had been killed.

Tomás Raymundo Cobo

Cajixay

Tu ko’me’ atikato’, tzitza’ kat kamkat aak vixq’ele’, kat k’achpu un k’uay nonajlik ta’n jal, eq’ol un vakaxh as kat ya’tz’pu k’ava’l un talintxa’, kat k’achpu voksa’m kajayil kat k’achpi as jitkuxh ta’ne’, kat tz’ejxu vatzik ta’n unq’a sole’. Vib’inaje’ Xhan Cham López, nimalkuxhe’ unq’a intza’le’ kat paltu yaab’e 1981. Na’ytza’Numike’ u kome’, as cheel ch’okuxhve’te’, tan kat tz’e’sali, nimal uxhchil kat kamí, echcole’ u vixq’ele’ tuk ka’va’l unq’aa un talin txa’; As kat e’q’ol u vatzike’, katilecha kat yatz’pukat.

***

Aquí mataron a mi esposa y quemaron mi troje llena de mazorca. Se llevaron mis vacas y mataron a mis dos hijos. Quemaron toda mi ropa, todo lo quemaron, además se perdió mi hermano, se lo llevaron los soldados. Él se llamaba Juan Chamay López. Muchas cosas pasaron en el año 1981. Antes aquí era una gran aldea pero ahora es pequeña porque fue quemada. Muchos murieron, mi esposa y mis dos hijos, luego secuestraron y asesinaron a mi hermano. Quién sabe dónde lo mataron.

***

Here they killed my wife and burnt down my granary full of corn. They took my cows and killed my two sons. They burnt all my clothes, they burnt it all, and even my brother went missing. The soldiers took him away. His name was Juan Chamay López. Many things happened in 1981. There was a big village here before, but now it is tiny because it was burnt. Many died: my wife, my two sons, and then they kidnapped and murdered my brother. Who knows where they killed him.

José Chamay

Amajchel

***

Tuyab’e 1982 kat uluq’a Chaxi’chalanaje’ tukukoome’ anikitza katchanaj tuvidestacamentoe’ tu xemak, Perla tetz tx’avul. Katulitz’esachanaj uq’aku kab’ale’ tulkatq’ab’i vatulchanaj katojveto’ jaq’tze’. Kat tze’kajayil, kuchikoje’ katitz’ok chanaj, katiyatz’chanaj talaku txokob’e, askat itz’esajchanaj q’oksam. Kat atinchanaj tukukoome’ oxval okajval ch’ich’, katchit itxakchanaj kajayil uq’aq’etze’. Unb’ie’ Kul tetzik akunb’ale’ ukab’ale’ vekat tze’i.

***

Fue en 1982, los soldados que llegaron a la aldea venían del destacamento de Xemac, la Perla, del municipio de Chajul. Vinieron a quemar nuestras casas y cuando oímos que venían huimos a la montaña. Quemaron todo, nuestras siembras las cortaron y mataron a nuestros animales, también quemaron nuestra ropa. Estuvieron en la aldea cerca de tres a cuatro horas, vinieron a barrer con todo. Me llamo Nicolás y la casa que aquí quemaron era de mi padre.

***

It was 1982; the soldiers that arrived in the village came from the Xemac detachement, La Perla, from the Chajul municipality. They came to burn our houses and when we heard they were coming we ran away to the mountains. They burnt everything, they razed our crops and killed our animals, and they also burnt our clothes. They were in the village for three or four hours, they came to sweep everything away. My name is Nicolás and the house they burnt here was my father’s.

Nicolás Cobo Raymundo

San Francisco Javier

Tu yab’e’ 1981, kat mox xe’t unq’a sole’ ti ik’achat unq’a kab’ale’ 1982 kat xe’t ikam unq’a uxhchile’ tit’ub’ul as echtuchile’ nikib’an chanaj, chajb’icha; kuj ni toon chajnaj ti’ i yatz’at unq’a xaole’, as tu o’laval tachb’al ich’e’ agosto ka u’lchajnaj ti’i yatz’at aak un b’ale’… Tul kam vun b’ale’ a kamal vinaj lavat xaol kat kami… ka maxku mujve´te askat b’enve’t’o’ tu tx’akab’e’n ve’ Ti’sumal, as kat mox q’ave’tzan o’ tu q’aatimb’ale un pajte’, as ye’lik ve’t unq’a uxhchile’ tu atimb’ale’, jatxelikve’t ivatz chajaak. Askat mox kave’to’ unb’il tu atimb’ale’, kat xe’t chanve’to’ ti’ku chicole’,qava chave’t ku ko’m, akole’ ka onchan ve’t unq’a sole’ tu yab’e’ 1984 kat mox b’enchanve’to’ un pajte’. Ine’ ye’ kat q’ave’t in tu vas vatimb’ale tan xe’xhkam atik ve’te’. Jaq’tz’an u ch’ooje’, tika’t kuxh nimox ixan kat unq’a a’e’ ye’lin kat q’ave’t in tu vatinb’ale’ tan un t’ub’uliko’ molonikq’ib’, yalin kat q’ave’lin.

***

En 1981 los soldados empezaron a quemar casas. En el año 1982 empezaron con las masacres. Así hacían, venían a cada rato y mataban a la gente y el 15 de agosto vinieron y mataron a mi padre. Cuando él murió, murieron cerca de 30 personas. Lo enterramos y nos fuimos a la montaña de Tisumal, allí estuvimos dos meses, después llegaron los soldados a Tisumal y volvimos otra vez a nuestro aldea pero la gente ya no estaba aquí sino que estaba dispersa. Nos quedamos un tiempo y cultivamos nuestra milpa, pero los soldados volvieron y en 1984 otra vez nos fuimos. Ya no regresé porque éramos un grupo. Antes de la violencia corría agua por donde quiera. Yo ya no regresé a mi lugar porque aquí ya no había nada.

***

In 1981 the soldiers started burning houses. In 1982 they started with the massacres. That’s what they did, they came every now and then and killed people and on the 15th of August they came and killed my father. When he died, another 30 people did too. We buried him and we went to Tisumal mountain, we were there for two months. However, the soldiers arrived in Tisumal and we went back again to our village but the people weren’t here anymore, they were scattered. We stayed for a while and farmed our corn, but the soldiers came back and in 1984 we left. I didn’t go back because we were a group. Before the violence water ran all over the place. I did not go back to my home because there was not anything left here anymore.

Juan Gaspar Raymundo

Xix

Alcancé a ver en otro bordito, y así cuando el ejército entró en la primera casa, lo rodearon la casa. Y como la señora que vivía en esa casa era la esposa de Don Fabían Ack’abal, ella se llama Catarina Tojín. Entonces en esto cuando tenía una hija y una nuera que estaba pues en visita, y las dos pues ellas se retiraron a sus casas, pero como el ejército la alcanzó a ver, y le correteó la señora Cristina y lo fue a alcanzar en el camino y lo machetearon la cabeza. Salió el seso, directamente se regó en el camino. Y la trajeron arrastrada y la fueron a encerrar en la casa de su mamá, de su suegra. Le echaron fuego a la casa y las ocho personas quedaron cenizado en la casa, directamente terminaron, único la barriga se quedó que no se quemó. Ahora, todos los huesos de la cabeza, los brazos, las piernas, todo se quedó cenizas. En esto que lo vi pues cuando quemó la casa y escuché los gritos allí adentro, bajo el fuego.

***

Kat ka’yikb’enin vi’ uma’l tal vitz as kat vil tok unq’a sole’ tu vaxa kab’ale’, kat isuturive’t chajnaj ti’ u kab’ale. Aak nane’ ve’ atik tu kab’ale’, a’ u tixq’el ak pap Fabian Ack’abal , vib’iiake’ Cat Toji, as aak nane’ atik uma’l vi xuakaak tuk’ uma’l u talib’aak nik iq’elun cha’mab’a as kat max b’enve’t cha’ma ti kab’al a’kole’ kat tilb’en u sole’ cha’ama, kat ilaq’b’a vet u sole’ aak nan Cristina, as kat itxiy ve’t chajnaj tu b’ey; kat ijatxk’u chajnaj vas ivi’e’ ta’n ch’ich’, kat ijitive’t chajnaj vas ichiole’ b’ex imuj ve’t chajnaj tikab’al vi txutxe’, utalib’e. As kat toksa ve’t chajnaj xamal ti’ u kab’ale’, uvaxiil uxhchile’ ve’ atik tu kab’ale’ kat mox tza’ajtuve’te’ tan xamal, kat max motx ta’n xamal, ta’nkuxh chaaxh tuule’ ye kat tz’e’i, echoj unq’a ib’ajil chaas ivi’e’, tuk’ unq’a iq’ab’e’, chaaxhtoje’ kayiil kat max tza’ajti. A’e’b’a unq’a intza’le’ kat mox vila tul uva’ kat max tz’e’ unq’a kab’ale’, kat vab’i sik’i’m tzitzi’ tu xamale’.

***

I managed to see over the side of the mound. The army went into the first house and they surrounded it. The woman that lived in that house was Don Fabian Ack’abal’s wife, her name was Catarina Tojín. Her daughter and her daughter-in-law were visiting, when they saw the soldiers they tried to go home but the soldiers caught them. They chased Señora Cristina and they grabbed her in the road and they hit her in the head with their machetes. Her brains were spilled all over the road. They dragged her and locked her up in her mother-in-law’s house. They set the house on fire and the eight occupants were reduced to ashes: they were all burnt, only the torsos remained, the heads the arms, the legs, everything was reduced to ashes. I saw the house burning while I heard the screams in there, inside the fire.

Tiburcio Castro

Fue el 16 de febrero del mismo año de 1982. Alcancé a ver que el ejército vienen corriendo, en el camino de Chalkaltzé. Alcancé ver a la señora cuando llegó en su casa ya, y lo agarraron la señora, lo acostaron sobre un trozo, y esa señora, pues, era ya embarazada, ya son momentos de dar a luz una familia, un bebé. Entonces en esto cuando, lo agarraron y lo cortaron la barriga, lo partieron así a la mitad de la barriga, y cuando en esto cuando le sacaron el pobre bebé que no ha llegado el momento de nacer, y ella se murió gritando allí, y el bebé lo agarraron y lo somataron en un tronco, allí se destalló el pobre niño.

***

Katib’an tu vajlaval tachb’al u ich’e’ febrero tu yab’e’ 1982 kat vila uva ooje’l chit i tzaa unq’a sole’ tu b’eye’ ve’t ti’tzaa tu chakaltze’, as kat untxol vilatb’en umal aak Nan uva b’iit kuxh toon tikab’al, tul kuxh oonaak tu vi kab’ale kat itxiy ve’t u sole’ aak, kat koxhb’a’l ve’t aak vi’ ma’l u tze’, as tu vas nane’ atik iyab’ilaak ti’ talintxa’, biitoj kuxh titz’e’b’ vas ine’ aakke’, tul uva’ kat koxhb’a’laak vi’ u tze’e’, as kat ijatxk’uchajnaj vas tuule’ spok’o’ch, kat teq’ove’t’eltzanchajnaj vas tal ne’e’, va ye’ onoj i q’ii ti’ titz’eb’e’ tzizi’ kat kamkat vas nane’ tuk’chit sik’ik, kat itxiy ve’t chajnaj vastal ne’e’ as ivuch’vet chajnaj ta’n tze’, tzitzi’ kat epkat vastal ne’e’.

***

It was February 16th, of the same year 1982. I managed to see the soldiers running from the road to Chalkaltzé in the distance. I could see a woman who was arriving at her house and they caught her. They laid her in a tree trunk; she was pregnant, just about to give birth. They cut her belly; they split her belly in half and took the poor baby out that wasn’t ready to be born. And she died screaming there, and they grabbed the baby and smashed it against a tree trunk. The poor kid burst there.

Tiburcio Castro

Chisis

Echtok unq’a chaxichalajnaje’ tub’eneb’al q’ii asatikin vatzq’anal tulmax iyatzchajnaj aak umb’ale tukaak untxutxe’ tukunq’a vatzike’ nimalchit ixaanchajnaj nimatunq’a patrulla xekelumpajte’ asun tzib’kuxh unkame’ xoleb’al akunb’ale tuk aakuntxutxe’ echikunkae txaq’tuchit veti’n taankaj, askamal tukitz’esain chajnaj nivalvete’, yenikuntxakvete’ asb’ex unmujvetb’ip’ tutxakab’en, ulchanin umpajte’ asun mujchab’etb’ip xoolunq’a kamchile’ umpajte’ unachvete’ uvayeluntxakvet uxamale’ asq’avchanin tutxakab’en umb’ajte. Lavalikuxh unyaab’ tzitzi. B’enb’etin tanva’lchit unxob’vet’ asva’lchit voq’e, unk’ulvetvip tukunmal akun nan b’enveti’n tiaak tulsajb’i asokuxh tunvi’ uvalaq’avin ti’b’envilat aakun b’ale’ tuk aakun txutxe’, tul onveti’n matikmax imutxvete’ akuxhchastee atikvetkan jank’alchit chasivatze’ q’echitvete’, chasumb’ale unq’a txi’e nimux.

***

Yo estaba en el patio cuando mataron a mis padres y a mis hermanos mayores. Alrededor de unos trescientos soldados y otros trescientos cincuenta patrulleros vinieron. Yo me hice la muerta, en medio de mis padres me quedé. Yo estaba llena de sangre y sentí que me iba a quemar, no aguanté más y me fui a esconder a la montaña, luego volví y me escondí con los que ya estaban muertos, pero sentí que ya no aguantaba el fuego y regresé a la montaña. Yo tenía como diez años, me fui con miedo y llorando, me encontré con una tía y me fui con ella. Cuando amaneció regresé al lugar nuevamente y vi a mis padres, estaban todos quemados. Sólo se les veían los dientes, toda la cara la tenían negra. A mi padre y a mi madre los perros ya les estaban comiendo las piernas, y mis hermanos ya no se veían quiénes eran y yo regresé llorando, ya no había nada que hacer y me fui.

***

I was in the yard when they killed my parents and my older brothers. Around three hundred soldiers and another three hundred and fifty patrolmen came. I pretended I was dead and stayed between my parents. I was covered in blood and I felt that I was going to be burned, I couldn’t stand it any longer and I went to hide in the mountain. Then I came back and hid among those who where already dead, but I couldn’t stand the fire and went back to the mountain. I was about ten years old, I left with fear and tears, I found an aunt and left with her. When dawn came I went back again to the place and I saw my parents, they were all burnt. You could only see their teeth; their whole face was black. The dogs where already eating my mother and father’s legs and you couldn’t tell who my brothers were anymore. I was crying, there was nothing left to do so I left.

Juana Ordoñez

Jakbentab

Unq’a Chaxi’chalanaje’ kat oon ti to’q’ol vun xuake’, txoom nik umb’ane va’vet kan kajayil bunka’e ve’ nuntxa’ankat, kat unchajnaj tun kab’al, matikvelch’uul kat vaq’kan unq’a vetz q’oon kuxh unb’ene kat itx’ey unq’a sole’ vun xake’, vinvinaj xhun, Juan Medina, kat txeypi as kat q’ispu viq’ab’e katkuxh b’enveti’n, kat va’kan uq’a vaq’omb’ale’, voksam, kajayilchituq’avetze’ kat tze’salvet tuk’ vun kab’al, kat tze’sal vun ixim pajte’ tuk’ vuntxikon. N imal exkat unb’anvete’ jaq’ tze’.

***

Los soldados vinieron a llevarse a mi hija. Yo estaba comiendo, dejé todo, mi piedra de moler donde comía, ellos llegaron a la casa, dejé todas mis cosas. Salí de la casa y me fui despacio. Los soldados agarraron a mi hijo, mi hijo se llamaba Juan Medina lo agarraron y le ataron las manos, yo me fui cuando agarraron a mi hijo. Tuve que dejar todas mis cosas, mis trastos, mi ropa, todo lo que yo tenía lo quemaron con mi casa. Hasta quemaron mi maíz y mi frijol. Me fui a esconder en la montaña durante mucho tiempo.

***

The soldiers came to take my daughter away. I was eating, I left everything, the grinding stone where I was eating, they turned up at my house, I left all my stuff. I went outside and walked slowly. The soldiers caught my son, my son’s name was Juan Medina, they caught him and tied his hands, I left when they caught my son. I had to leave all my stuff, my things, my clothes; everything I had was burnt with the house. They even burnt my corn and bean crops. I went to hide in the mountains for a very long time.

Teresa Gómez Rodríguez

Xexocom

***

Tu yab’e 1981 kat tilulo’ tan inq’a Chaxi’chalanaje’, kat yatzpu’ tenam, ku txocop, aka’tx, chicham, vakash, tzok’pu ku koom katchit i txak kajayil. Kab’lavalik un yaab’ yeshkam ikvete kamkuxh kat kuleja’ tu txakab’en kat q’exhb’uvete, kam kuxh itzaj, kat q’exhb’uvete, kat ok ku yab’il, nimal chaak kat kam jaq’tze. Atik mal uvatzik La’s (Francisco)ib’ii kat chib’ii kat ch’ooni’ as kat kam vete kaat inq’a vitzine’ Ann tuk u Te’k ye kat i tx’ol imujatib’ kat onn inq’a sole’, kat itxakb’a vi umal u k’ub’ as kat jub’ali’ tuk pixhul u nailo, xonlik in kat un b’an invate jaq’ chit u jab’ale kat un txeb’ isajb’e. nik un txuq’txune tul ni telch’ul u q’ii, as nik i tx’ak in u va’ye tuk u txumum.

***

En el año de 1981 nos persiguieron los soldados, mataron a la gente, nuestras mascotas, pollos, cerdos, vacas, cortaron nuestras siembras de milpas, acabaron con todo. Yo tenía como 12 años. Como ya no teníamos nada comíamos lo que encontrábamos en la montaña, cualquier clase de hierba, nos desnutrimos y muchos murieron en la montaña. Tenía un hermano llamado Francisco Marcos, se enfermó y murió de hambre, a mis hermanos Ana Marcos y Diego Marcos que no lograron esconderse se los llevaron, los pararon sobre una piedra y les dispararon. Con un pedazo de nylon y sentado intentaba dormir bajo la lluvia hasta el amanecer, me ponía feliz cuando empezaba a salir el sol pero a la vez me ganaba el hambre y la tristeza.

***

In 1981 the soldiers chased us, they killed the people, our pets, chickens, pigs, cows, cut our crops of corn fields, destroyed everything. I was about 12 years old. As we had nothing to eat we ate what we found in the mountains, all kinds of grass; we were malnourished and many of us died in the mountain. I had a brother called Francisco Marcos, he got sick and starved to death. My siblings Ana Marcos and Diego Marcos, who failed to hide from the soldiers, were captured. The soldiers made them stand on a rock ‘and shot them. Under a piece of nylon I tried to sleep till dawn. When the sun began to rise I would get happy, but immediately after I felt hungry and sad.

Juan de Paz Marcos

Chemal

Kat òolin xol uvitze’, o’laval q’ii kat q’ospin asnimal chitkat kaxb’ilin, kat q’itzpin, junq’ichit nunq’osb’e, tumal uq’ii vatik chanaj katún txolvoje’ q’itzelikin tulkat oojin kat tilchanaj askati jub’ain chanaj vi’un cheleb’ k’axb’inalchitveti’n, o’laval uq’ie katulkati’n sunjunal katt ku’in tumal uju’l ye’nun txo’lvet unje’chu’l, kamkuxh niva’vetku’ tukun k’axb’ichile’ eche’ xajkuach a’nikunsa’ valatxanike’, tulkat untxo’l velchu’l q’oonkuxhvet untzae xol uvitze’. Tulkat ulin tunkab’al kat koxheb’in askat itza’kavetin akun txutxe’. Kat ulchanvetchanaj tuyab’e 1982 askati tz’esachavet chanaj ukab’ale’. Katib’ana tu oval chi’ch tuq’alame’ katvil itzachanaj askat valvet ti’ akuntxutxe’, ta’l nikib’anaki katkuxh ta’vetkanaak tzitzi katb’enchanvet’o jaq’tze’.

***

Me llevaron entre las montañas, por quince días me pegaron y me lastimaron mucho. Me amarraron. Todos los días era lo mismo, me pegaban, pero un día cuando ellos se durmieron me escapé. Estaba amarrado y cuando corrí ellos se dieron cuenta y me dispararon en el hombro. Estaba muy lastimado, tardé quince días en regresar a casa. Me caí en un hoyo y ya no podía salir, en mi herida me echaba cualquier cosa como musgo con tal de curarme. Cuando logré salir del hoyo me vine despacio entre las montañas. Llegué a mi casa y me acosté; mi madre muy preocupada me curaba. Volvieron en 1982 y quemaron la casa. Fue a eso de las cinco de la mañana, me di cuenta de que venían y le avisé a mi madre. Ella estaba cocinando, dejó el desayuno allí y huimos a las montañas.

***

They took me to the mountains and for a fortnight they hit me and hurt me a lot. They tied me up. Everyday it was the same, they hit me, but one day when they fell asleep I escaped. I was tied and when I ran, they realised and shot me in the shoulder. I was really injured; it took me a fortnight to get back home. I fell in a hole and I couldn’t get out, I would put anything in my wound, like moss, just to try and heal myself. When I was able to get out of the hole I came slowly through the mountains. I arrived home and I lay down and my very concerned mother healed me. They came back in 1982 and they burnt down the house. It was about 5 in the morning, I realised they were coming and I told my mother, she was cooking but she left the breakfast and we ran into the mountains.

Mateo Toma Perez

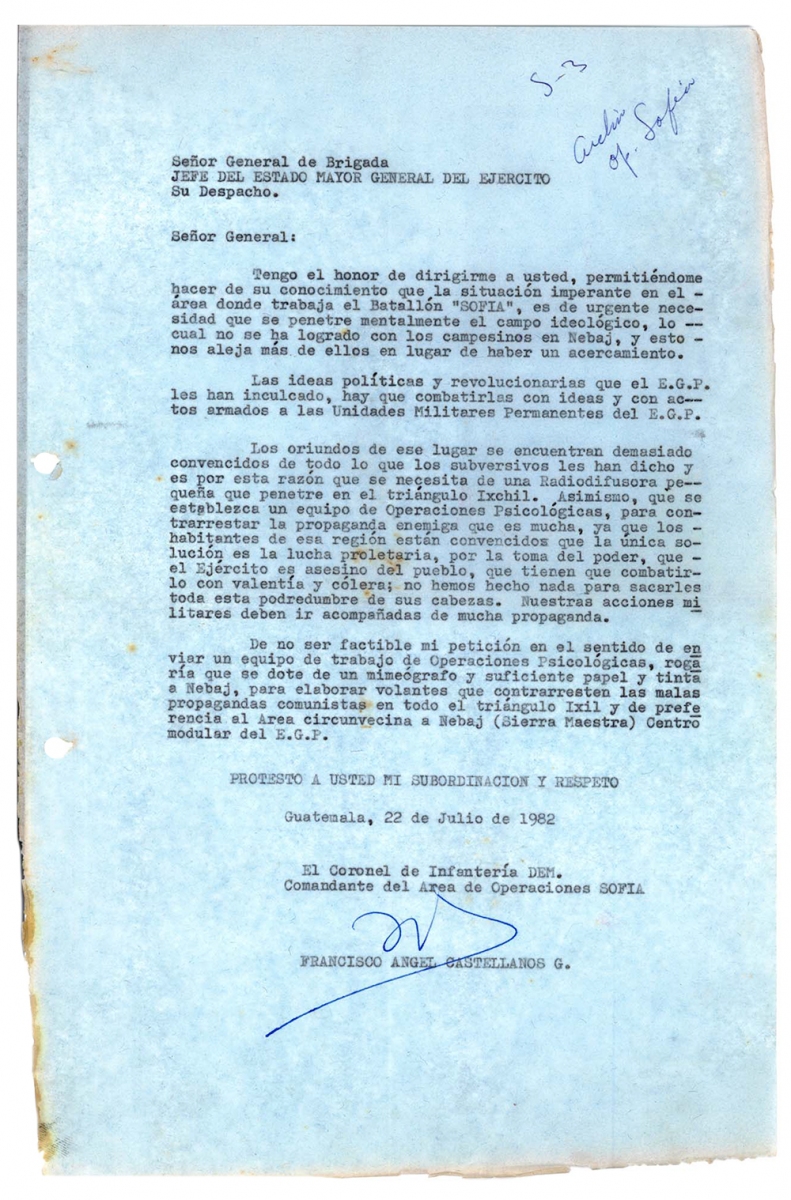

Doscientos mil es la medida de la infamia. Es el saldo de muertos durante el conflicto armado en Guatemala. Otros 40 mil fueron desaparecidos. Ambos números fueron el efecto de la Guerra Fría en Centroamérica y el resultado de sus tácticas de “baja intensidad”. Es decir, las acciones militares contrainsurgentes realizadas durante un período de 36 años, entre 1960 a 1996, que marcaron la historia de este país centroamericano situado en la frontera sur de México. Entre 1981 y 1983, agentes del Estado de Guatemala cometieron actos de genocidio en contra de su población y, en particular, de grupos del pueblo maya y del área rural del altiplano. Esta estrategia no sólo dio lugar a la violación de los derechos humanos esenciales sino a la ejecución de crímenes masivos, reconocidos hoy bajo los arquetipos de las masacres y las estrategias de tierra arrasada. Ambos fueron actos de ferocidad que antecedieron, acompañaron o siguieron a la muerte de las víctimas. En otros circuitos y tiempos, esta estrategia se describía en la frase de “quitarle el agua al pez” y en la lección aprendida por Estados Unidos tras la experiencia en Indochina y las dos etapas de contrainsurgencia en Vietnam (1961-63 y 1969-75): una capacidad militar superior contra un adversario compuesto de fuerzas irregulares y populares no es ninguna garantía de victoria. Quitarle el agua al pez consistió en eliminar todos aquellos recursos –humanos especialmente- que pudieran levantar sospechas, de ayuda a la sobre vivencia de la insurgencia, apoyar su capacidad de movilización y suministrarle equipo de combate, alimentos, atención médica y otros medios. En Guatemala, las Tierras arrasadas fueron la garantía de una paulatina asfixia de los grupos rebeldes.

Los calmos paisajes de Óscar Farfán parecen no dar cuenta de ese tremendismo. Las piezas que comprenden este proyecto -fotografías, textos y video- operan como registros de esos sitios pero en un estado de silencio que parece contradecir lo acontecido en ellos. El artista es de origen guatemalteco y esta es su forma de arrancar las palabras –probablemente dichas de muchas víctimas de las masacres antes de morir- al silencio. También es una forma de volver a un país que, en cierto sentido generacional, le resulta desconocido. En esta oportunidad, el espacio del arte permite ese proceso de “volver”, de reconocimiento y de denuncia de lo que fue la instauración y perpetuación de los mecanismos de terror en Guatemala.

El paisaje, en su noción artística y fotográfica, fue el cromo de la contemplación de lo incivilizado por excelencia. La noción de paisaje nació a partir de una mirada condescendiente sobre lo rural, sobre esa forma de vida que se alejaba en razón del crecimiento de las ciudades y la experiencia urbana. Estos paisajes hermosos van más allá del puro documentalismo y el placer de fotografiarlos. Tierra arrasada es un proyecto que intenta girar la tuerca de la historia, para colocar al espectador frente a espacios que no tienen nada de simulacro. Pero que, por rurales, tienden a ser negados y olvidados.

Rosina Cazali. Guatemala, 2011.